Chinese New Year Worksheets

All About These 15 Worksheets

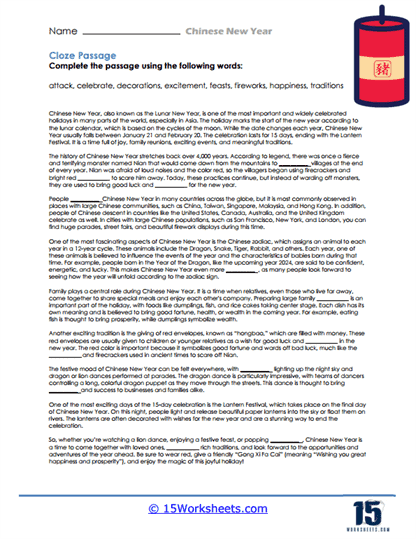

Our Chinese New Year worksheets will engage students and children in learning about the Chinese New Year, also known as the Lunar New Year or Spring Festival. These worksheets cover a wide variety of activities and exercises that aim to enhance students’ understanding of the cultural, historical, and social significance of this important holiday. They also introduce key concepts such as the Chinese zodiac, traditional customs, symbols, and the festival’s global importance.

These worksheets include exercises that incorporate literacy, numeracy, cultural learning, arts and crafts, critical thinking, and creativity. They serve a dual purpose – not only do they educate students about the specifics of the Chinese New Year, but they also reinforce academic skills like reading comprehension, problem-solving, vocabulary building, and even basic math. These worksheets can be tailored for different age groups, from preschoolers to older students, offering exercises that range from basic coloring pages to more complex assignments like writing essays or researching historical facts.

This collection of worksheets for kids is designed to provide a comprehensive and engaging exploration of the holiday, helping students understand its cultural significance, traditions, and symbols. Given the multifaceted nature of the Chinese New Year celebration, Chinese New Year Worksheets often come in a variety of formats and exercise types. These include activities that involve literacy, numeracy, arts, critical thinking, and hands-on creativity. Here’s a breakdown of the learning objectives and activities across the various worksheets:

Introducing the Concept – The first set of worksheets will introduce students to the basics of Chinese New Year, including the origins, significance, and widespread celebration of the holiday. Students learn about traditions like family gatherings, decorations, and fireworks, along with the meaning behind these customs. This serves as a foundation for understanding the 15-day long festival.

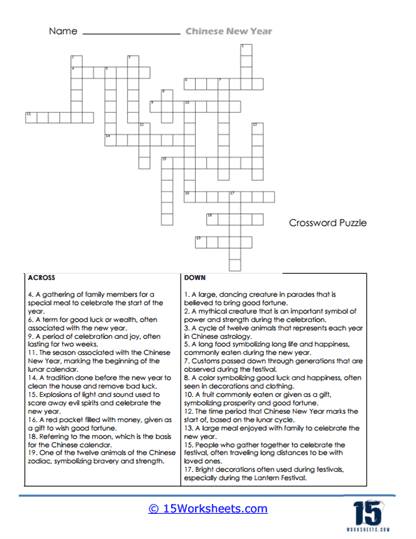

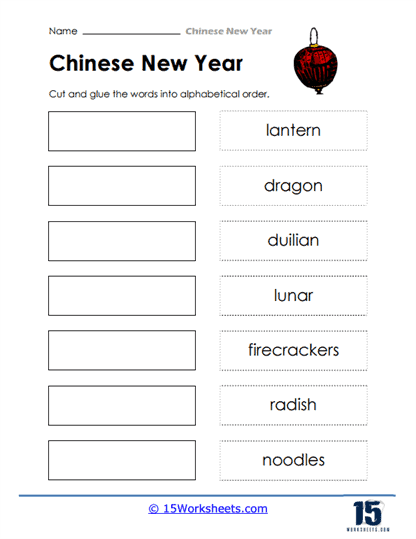

Language Puzzles – A crossword puzzle reinforces key vocabulary and concepts related to Chinese New Year. Students use clues to fill in words associated with the holiday, such as “dragon dance,” “lantern,” and “firecrackers.” This activity strengthens their retention of important terms and ideas through an interactive format.

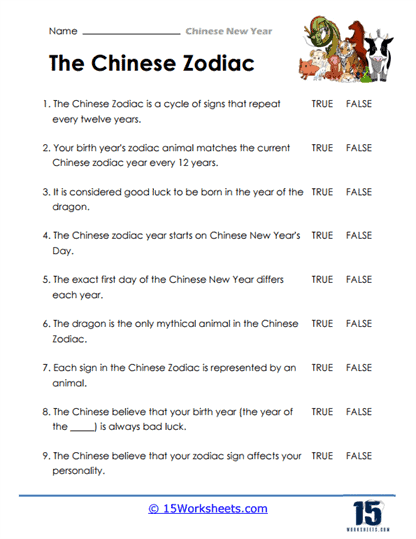

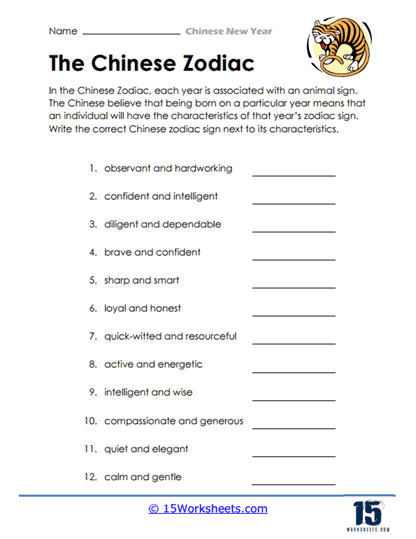

The Chinese Zodiac – A true or false worksheet about the Chinese Zodiac teaches students about the 12-year cycle of animals that represent each year. The activity helps them understand the cultural importance of zodiac signs in determining personality traits and predictions. The worksheet encourages critical thinking as students discern between correct and incorrect statements.

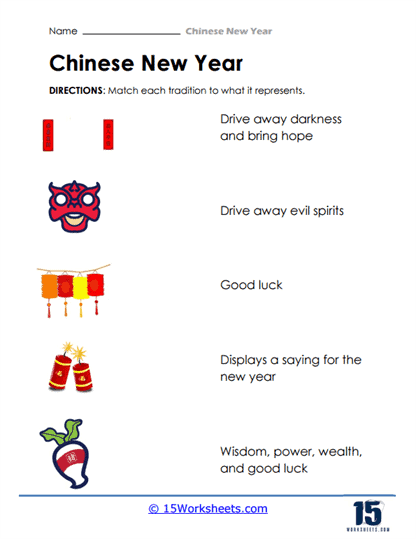

Symbol Matching – In a matching activity, students connect traditional Chinese New Year symbols, such as firecrackers, lanterns, and the dragon, with their meanings, such as good luck, driving away evil spirits, and hope. This visual exercise helps students grasp the symbolic meanings behind different customs and reinforces their learning in a creative way.

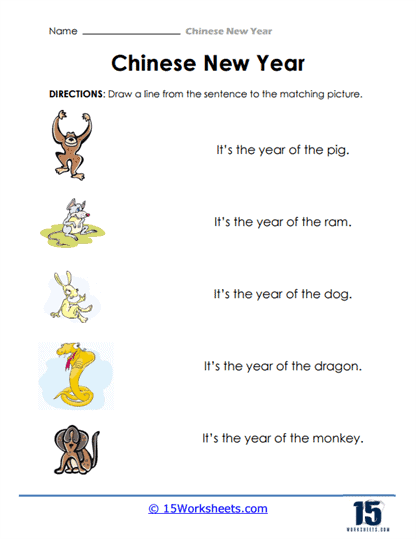

Zodiac Personality Traits – These worksheets focus on linking each Chinese Zodiac animal with personality traits such as “brave and confident” or “loyal and honest.” By doing so, students learn how different animals are believed to influence the characteristics of individuals born in those years, deepening their understanding of the Zodiac’s cultural role.

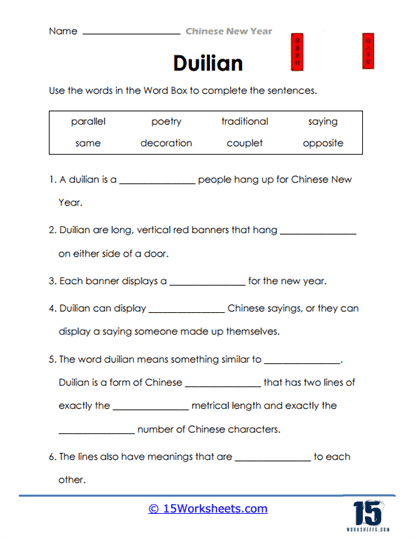

Duilian (Poetry Couplet) – A fill-in-the-blank worksheet on “Duilian,” the decorative red banners hung during Chinese New Year, explains their meaning and form. Students are asked to complete sentences about duilian, learning about the importance of the poetry and messages displayed for the new year. This activity highlights the cultural significance of traditional decorations.

These worksheets combine reading, vocabulary building, matching, and puzzles to engage students in a variety of learning activities. Each worksheet focuses on different aspects of Chinese New Year, from its origins and traditions to the symbolism behind decorations and the Chinese Zodiac. Together, they provide a well-rounded and immersive learning experience, helping students connect with the cultural and historical context of this widely celebrated holiday.

What is Chinese New Year?

Chinese New Year, also known as the Spring Festival (春节, Chūn Jié) or the Lunar New Year, is one of the most significant traditional holidays celebrated by the Chinese people and many other East Asian cultures. It is a time of family reunions, feasting, and cultural activities that are steeped in thousands of years of history and rich traditions. The festival marks the beginning of the lunar calendar, with celebrations that last for about 15 days. Let’s explore the history, timing, global celebrations, unique aspects, and customs that make Chinese New Year such an important and fascinating event.

Historical Origins

The roots of Chinese New Year can be traced back over 3,000 years, evolving from ancient agrarian festivals in China. Traditionally, it was linked to the lunar-solar Chinese calendar, which dictated the cycles of farming and the seasons. During the Shang Dynasty (1600–1046 BCE), it is believed that people held religious ceremonies to honor gods and ancestors, seeking blessings for a good harvest in the coming year. By the time of the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE), the celebration was more formalized, and the concept of beginning a new year at the end of winter started to solidify.

The mythology surrounding Chinese New Year is also deeply woven into its history. One of the most famous legends is about a beast called “Nian” (年), which lived in the mountains or under the sea and would come out on the last night of the lunar year to attack villages, devouring crops, livestock, and even people. The villagers eventually discovered that Nian was afraid of loud noises, bright lights, and the color red. To protect themselves, they began lighting firecrackers, hanging red lanterns, and decorating their homes with red couplets-traditions that have survived into modern times.

Chinese New Year has undergone various transformations over the centuries. The Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) saw the formalization of the lunar calendar, and during the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), the festival expanded to become a grand, nationwide celebration. By the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912), many of the customs and traditions we recognize today had already taken shape, including the giving of red envelopes (hóngbāo), family feasts, and temple visits.

Timing of Chinese New Year

The date of Chinese New Year is not fixed because it follows the lunisolar Chinese calendar, which is based on both the cycles of the moon and the sun. The festival typically falls between January 21 and February 20, depending on the year. The celebrations start on the first day of the lunar year and last until the Lantern Festival on the 15th day, which marks the end of the Spring Festival.

The timing of the New Year marks the end of winter and the beginning of spring, symbolizing renewal and new life. The Chinese Zodiac, which operates on a 12-year cycle, assigns an animal to each year (Rat, Ox, Tiger, Rabbit, Dragon, Snake, Horse, Goat, Monkey, Rooster, Dog, and Pig), and each year is also associated with one of the five elements (Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, and Water). This combination of animal and element influences the characteristics of the year, adding further meaning to the celebration.

Who Celebrates Chinese New Year?

Chinese New Year is celebrated primarily in China, but it has also become a major holiday in many other countries with significant Chinese populations, such as Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, the Philippines, and even in Western countries like the United States, Canada, and Australia. In Vietnam, the celebration is known as Tết Nguyên Đán or simply Tết, while in Korea it is called Seollal, and in Tibet it is known as Losar. Each culture has its own unique customs, but the core themes of family, renewal, and prosperity remain consistent across these celebrations.

In major cities across the world, Chinese New Year parades and public festivals have become widely popular, often featuring lion dances, dragon dances, fireworks, and cultural performances. In places like New York, San Francisco, London, and Sydney, Chinese communities organize vibrant street festivals where both locals and tourists join in the festivities.

Unique Aspects of Chinese New Year

One of the most unique aspects of Chinese New Year is its emphasis on family and togetherness. The holiday begins with the practice of “getting home” (回家, huí jiā), a time when millions of people across China embark on what is known as the largest annual human migration, as they travel to their hometowns to reunite with their families. The importance of family is underscored by the traditional New Year’s Eve reunion dinner (年夜饭, nián yè fàn), where multiple generations gather around the table for a lavish meal.

Symbolism is woven into almost every aspect of the holiday. The color red, for example, is believed to ward off evil spirits and bring good fortune. Red decorations, such as paper cuttings and banners with auspicious phrases, are hung throughout homes and public spaces. Fireworks and firecrackers, which originated from the need to scare away the mythical Nian, are another iconic element of the holiday. On the stroke of midnight, they are set off to usher in the New Year with a bang, believed to drive away bad luck and evil spirits.

Another unique element is the use of the red envelope, or hóngbāo (红包). These red packets contain money and are given to children, unmarried relatives, and sometimes even employees as a gesture of good luck and blessings for the New Year. The act of giving a red envelope symbolizes the sharing of wealth and prosperity.

Food plays an essential role in the celebrations, with each dish carrying symbolic meaning. Dumplings (饺子, jiǎozi), which resemble ancient Chinese currency, symbolize wealth, while fish (鱼, yú) is served because it sounds like the word for “surplus,” representing abundance. Other foods like rice cakes (年糕, niángāo) and tangyuan (汤圆, sweet rice balls) are consumed for their associations with rising fortune and family unity, respectively.

Customs and Traditions

The customs and traditions surrounding Chinese New Year are a rich tapestry of ancient practices that have been adapted to modern life. The celebration can be divided into three phases – the preparations, the New Year celebrations, and the post-New Year activities.

Preparations (before New Year’s Eve) – In the days leading up to the New Year, families thoroughly clean their homes in a ritual known as “sweeping the dust” (扫尘, sǎo chén), which symbolizes removing bad luck and misfortune from the previous year. This cleaning is essential because it is believed that cleaning during the New Year period itself could accidentally sweep away good fortune. After cleaning, homes are adorned with red decorations, such as couplets, paper cuttings, and lanterns. People also make offerings to the Kitchen God (灶王爷, Zào Wáng Yé), hoping that he will report good things about the household to the Jade Emperor.

New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day – The highlight of Chinese New Year is the reunion dinner on New Year’s Eve. This meal is incredibly symbolic, with dishes carefully chosen for their meanings. Families often stay up late on New Year’s Eve, a practice known as “shǒusuì” (守岁), which is believed to help bring longevity to one’s parents. At midnight, firecrackers are set off to welcome the New Year, and many families burn incense and pray to their ancestors.

On New Year’s Day, people dress in new clothes, often in red, and visit relatives and friends to exchange greetings and gifts. A common greeting during this time is “Gōng Xǐ Fā Cái” (恭喜发财), which means “wishing you wealth and prosperity.” It is also considered important to start the year by avoiding bad omens; arguments, breaking things, or using unlucky words are strictly avoided.

Post-New Year (up to the Lantern Festival) – The celebrations continue for several days, with visits to friends and extended family. On the fifth day, known as the “Birthday of the God of Wealth” (财神, Cáishén), businesses often reopen and set off firecrackers to attract prosperity. The final major event of the New Year is the Lantern Festival (元宵节, Yuánxiāo Jié), held on the 15th day. This day is marked by the lighting of colorful lanterns, lion and dragon dances, and the eating of tangyuan (glutinous rice balls), symbolizing family unity.